I got a loom! Now I can weave! Right?

Not so fast.

Not only do I not have yarn, but the loom is missing some parts, and I don’t know enough about looms to know what’s missing.

I momentarily wonder if I’ve made a huge mistake. What if I never figure out what this thing needs, and it turns out to be a lemon?

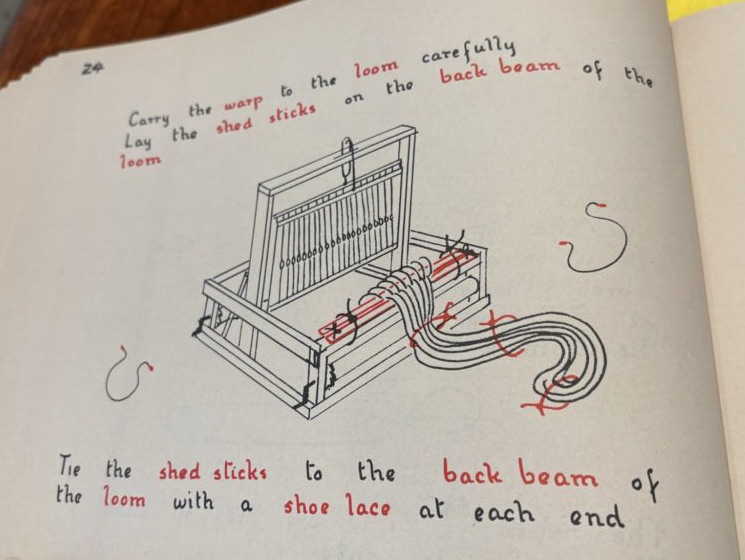

You Can Weave doesn’t have anything specific to say about what to do with the funky old loom you bought at a bike repair clinic. But I can pick out cases where Bessie and Mary have outlined what to do, if you don’t have exactly the thing you’re meant to have.

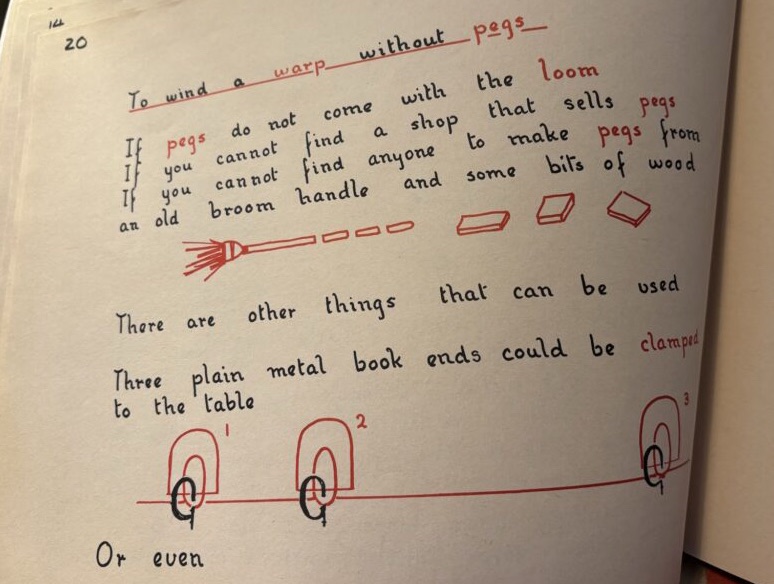

I’m especially fond of the illustrated explanation on page 20, suggesting how to make pegs out of an old broomstick, or a few plain metal bookends. (Bookends! How exciting. I’m not sure it’s easier to find plain metal bookends than pegs, in 2025.)

Weaving is an old technology. We can apparently find suggestions of weaving as far back as the paleolithic age, 27,000 years ago. It shows up in ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian art, the Inca civilization, and tombs from the bronze age, in China.

There’s no known causal link between all our cultures and learning to weave. It’s a primordial tech solution everyone figured out independently, in response to having both fibre, and a need to wrap something– usually people, either the living or the dead.

on Flickr.

People have been improvising looms for centuries (and still do today), using whatever they had around, in whatever way made sense in their culture. Seen through that lens, my incomplete loom is a head start, not a hinderance.

How much of a head start do I have? Let’s evaluate.

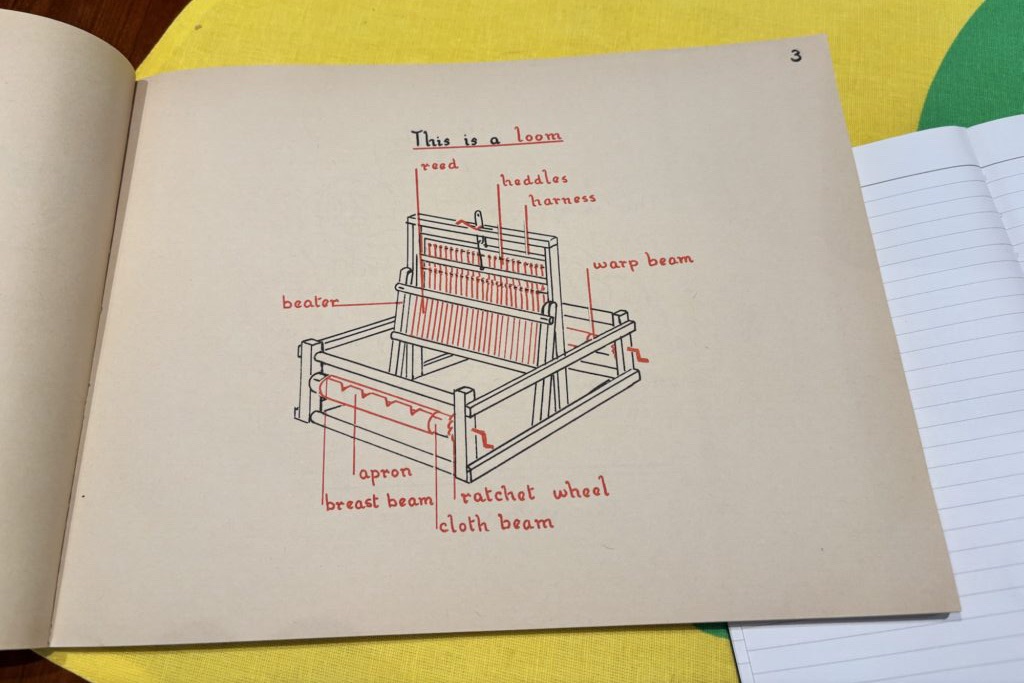

A table loom mainly has the job of using multiple shafts to raise and lower x-axis strands of yarn on a z-axis, so that y-axis strands of yarn can be passed back and forth through it on the perpendicular, at user-defined intervals, to create an interlocking weave that becomes fabric. The x-axis strands must be held with tension, and they need to advance from the back to the front of the loom on rollers, so you can control your materials, and gather up your product.

How well your loom performs each of those functions has a bearing on the physical and aesthetic quality of the fabric produced. But it’s not the only factor. You, your ideas, skills, and consistency, are part of the equation. This relationship between person and machine is one I already know, from playing musical instruments, and operating an espresso machine. I’m comfortable with it.

My loom appears to have the most important bits. Maybe not in an ergonomic configuration, possibly not calibrated precisely, but fine for learning. My attention to the loom will become a third factor in what I’m able to make.

Now let’s take a look at the nonstandard features of this loom:

It doesn’t have levers to help raise and lower the shafts. It has four holes, and makeshift hooks. The previous owner appears to have been using yellow yarn to control the shafts. It seems like yarn would brake frequently and be fussy to use here.

The shafts also don’t have tracks to sit in. They just kind of dangle and bump into each other.

There’s no back beam. It has a big turny thing instead (technical term), which doesn’t seem to match any tutorials I can find so far. I think I can work with it, but the Big Turny Thing ™ also doesn’t have a brake. I’ll need to improvise something for tension.

The rods in front and back appear to be made of wooden dowling. I expect this means it will bend more than a metal rod, creating uneven tension, in places. And the front rod is attached to the front roller at uneven intervals.

It’s tempting to try to fix everything, but I don’t want to do that, before I understand how the machine works. I also read more than once, that many weavers fall so deeply into the hole of fixing or perfecting their looms, that the loom becomes the project and no weaving gets done.

This sounds exactly like something I would do, so I resolve not to do it. To brake the back roller (Big Turny Thing), I’ll experiment with various cords, bungees and wooden stakes until I find something that works. I’ll focus on improving the shaft control mechanism.

I work out a hack where I replace the yellow yarn with stronger-yet-terrible nylon cord from the dollar store, and loops of zip tie, so I can more easily hook and unhook the cords when I raise and lower the shafts.

This single fix takes me a couple of hours to orchestrate, after trying a few kinds of knot that don’t work. I ultimately have to melt the nylon a bit to get it to bind to itself and stop unwinding.

By the time I’m done, I’m equal parts tired, fed up, sweaty, and extremely satisfied with myself. I admire my work, and decide to name my loom Frankie. Frankie the Frankenloom.

Now all I need is yarn. And a shuttle. I order them, and wait.

You Can Weave – archives

- January 2025 (3)