You Can Weave: Let’s Get Warped

I detail my plans for creating a Montreal Tartan, and make my first warp– that’s the long vertical threads– for the loom, with Penelope’s help.

I detail my plans for creating a Montreal Tartan, and make my first warp– that’s the long vertical threads– for the loom, with Penelope’s help.

My new-old loom needs some work to make it usable. It also gets a new name.

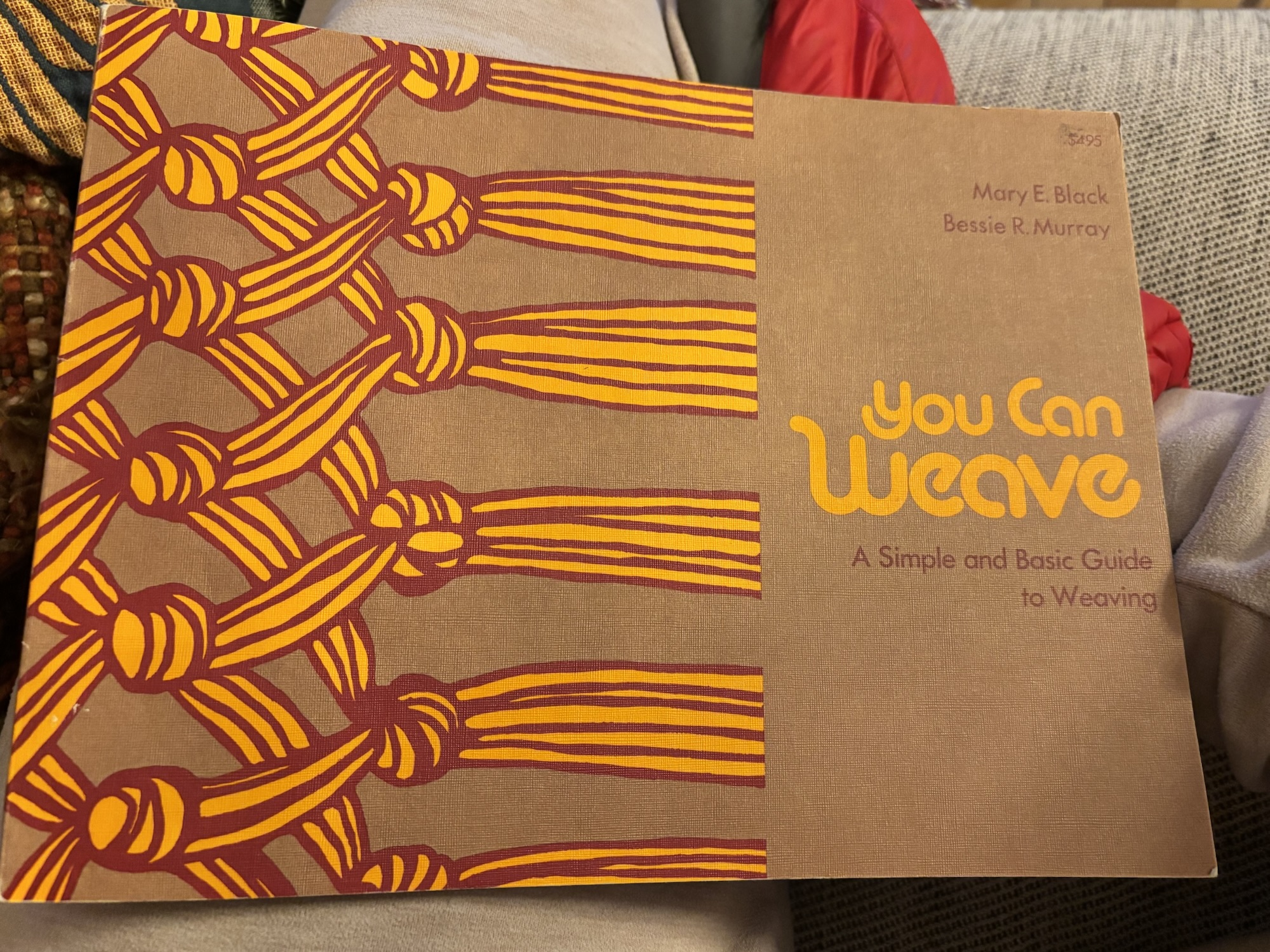

In which I embark on a major project to learn from a book my grandmother co-wrote, in 1974.